Board of 4 Persons (High Representative of disarmamanet affairs, chairman, secretary, IAEA).

International Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Law as Part of International Law (I)

What is international law?

International law is the body of norms governing the relations between its subjects. This includes states, first and foremost, but also others, such as international organisations.

International law regulates different fields of cooperation ranging from terrorism, outer space and global communications to human rights, the environment and non-proliferation and disarmament.

How are international law and non-proliferation and disarmament law related?

International non-proliferation and disarmament law forms part of international law and is one of its many “sub-regimes”. The founding and functioning principles of non-proliferation and disarmament law are therefore aligned with those of international law.

This holds true with regard to:

- the sources of international non-proliferation and- disarmament law

- its subjects

- its application

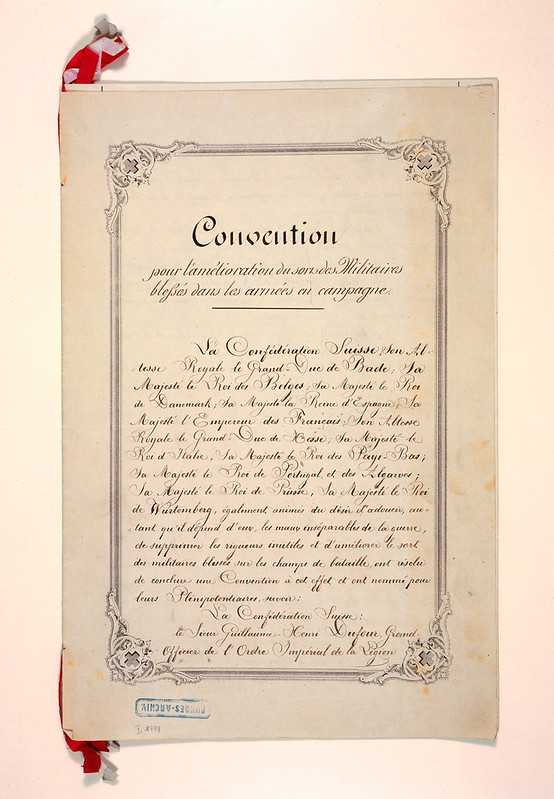

Scan of convention.

Do international law and international non-proliferation and disarmament law really work?

The flaws of international law often show in dramatic and difficult situations such as wars and severe political and social upheaval. These shortcomings receive much attention in the media, causing public opinion to question the usefulness, or sometimes even existence, of international law.

However, as noted by renowned scholar Louis Henkin,

almost all nations observe almost all principles of international law and almost all of their obligations almost all of the time. As the “100 Ways” project described in the next section demonstrates, almost all of the time we may just not be aware of it.

Louis Henkin.

Moreover, even at such challenging times as armed or political conflict, states consistently seek to justify their acts on the basis of international law. This demonstrates that states consider themselves bound by the rules they have set, whatever the circumstances.

During certain periods of time or certain events, states may deny and defy international law, but this will almost always come at a political or economic cost in their relations with other states.

The 100 Ways project of the American Society of International Law shows that international law is so deeply and comprehensively ingrained into everyday life that its existence can be easily overlooked. The project gives a 100 examples of how international law works across eight areas: daily life, leisure, travel, commerce, health and the environment, personal liberty, safety and development, and peace and security.

To give one such example, mailing a postcard to any country across the globe is easy, because of the 1964 Constitution of the Universal Postal Union, which sets up a worldwide postal network and ensures that the stamp you bought is recognised for mail delivery by all other states.

As for peace and security, another example is “banning cruel and inhumane weapons such as sarin gas” (International Law: 100 Ways It Shapes Our Lives ). This is done by a number of treaties including the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention and the 1972 Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention. These treaties form part of international non-proliferation and disarmament law.

Sources of International Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Law

This video lecture covers the following topics:

- the legally binding sources of international non-proliferation and disarmament law

- the “soft law” sources of international law

Sources: Legally Binding and Non-Binding Instruments

Binding or “hard law”: Creates obligations and rights

- Treaties: eg. Chemical Weapons Convention

- Custom: eg Prohibition of use of biological weapons

- General principles: eg good faith

- Judicial decisions and teaching of the most qualified publicists: eg International Court of Justice cases

Non-binding or “soft-law”: gives guidance and recommendations and may be incorporated into legally binding internationan or national instruments

- UN General Assembly resolutions: eg Resolution 74/66: Strengthening and developing the system of arms control, disarmament and non-proliferation treaties and agreements

Codes of Conduct, Guidelines

eg IAEA Code of Conduct on the Safety and Security of Radioactive Sources

Legally Binding Sources: Examples of Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Treaties

The treaties mentioned on this page aim to prohibit so-called ‘weapons of mass destruction:’ biological, chemical, nuclear and radiological weapons. They also aim to control the materials that may be diverted from peaceful activities in science, medicine and industry to make such weapons. They are legally binding on states that have joined them: they create rights and obligations for those states.

Biological weapons and materials

- 1925 Protocol for the Prohibition of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare

- 1972 Convention on the prohibition of the development, production and stockpiling of bacteriological (biological) and toxin weapons and on their destruction (BWC)

See also (LU 03: Biological Weapons) []

Chemical weapons and materials

- 1925 Protocol for the Prohibition of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare

- 1993 Convention on the prohibition of the development, production, stockpiling and use of chemical weapons and on their destruction (CWC) See also (LU2: Chemical Weapons) []

Nuclear and other radioactive material

- 1956 Statute of the International Atomic Energy Agency

- 1968 Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), and regional nuclear weapons free zones treaties

- 1980 Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material (CPPNM)

- 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT)

- 2005 International Convention for the Suppression of Acts of Nuclear Terrorism (ICSANT)

- 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW)

See also (LU05:Nuclear Weapons II) [] and (LU07: CBRN Terrorism) [].

Legally Binding Sources: Focus on the Chemical Weapons Convention

The CWC is an interesting example of a legally binding source of non-proliferation and disarmament law. It prohibits an entire category of weapons. While toxic chemicals can be misused to develop these weapons, states have the right to undertake peaceful activities with these chemicals; including for industrial, agricultural, research, medical and pharmaceutical purposes. Moreover, the CWC establishes an international organisation tasked with verifying that chemical weapons have been destroyed and that states’ activities with toxic chemicals remain lawful.

You can read more about the CWC’s history in our learning unit on chemical weapons.

In comparison, the BWC also bans a category of weapons and encourages the peaceful uses of biological agents and toxins, but it does not create an organisation to verify its application. The NPT encourages the peaceful uses of nuclear energy, but it does not ban nuclear weapons for all states. It delegates verification activities to the IAEA , an organisation that pre-dates the treaty.

The CWC comprises 24 articles and 3 annexes for a total of 165 pages. In comparison, the BWC comprises 15 articles, and the NPT 11.

The CWC includes different categories of provisions:

- provisions common to most treaties: preamble, definitions, general obligations, settlement of disputes, amendments, duration and withdrawal, conclusion and entry into force, reservations, depositary (see Chapter 2) for more information about treaty law)

- provisions specific to the subject matter: declarations, chemical weapons, chemical weapons production facilities, activities not prohibited under the convention, economic and technological development, assistance and protection against CW, annexes on verification and confidentiality

- national implementation measures

- mechanisms to raise and redress situations of non-compliance

- institutional provisions establishing the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, its mandate, structure, and privileges and immunities

Legally Binding Sources: Focus on UNSCR 1540 Decisions

UN Security Council Resolution 1540 was adopted in 2004 and addresses the non-proliferation of nuclear, chemical and biological weapons (as well as their means of delivery) to non-state actors.

UNSCR 1540 was adopted under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations which authorises the UN Security Council to take enforcement action with respect to situations it considers threats to the peace, breaches of the peace, and acts of aggression. The proliferation of nuclear, chemical and biological weapons to non-state actors was considered a threat to international peace and security.

UNSCR 1540 is a resolution, not a treaty. However, it includes legally binding decisions. This is pursuant to Article 25 of the UN Charter, which stipulates that UN members agree to accept and carry out the decisions of the Security Council. The following are such decisions in UNSCR 1540:

- All States shall refrain from providing any form of support to non-state actors that attempt to engage with nuclear, biological and chemical weapons.

- All States shall adopt and enforce laws prohibiting any non-state actor to manufacture, acquire, possess, develop, transport, transfer or use these weapons and their means of delivery.

- All States shall take and enforce measures to establish domestic controls to prevent the proliferation of these weapons and their means of delivery.

UNSCR 1540 relationship with other non-proliferation and disarmament instruments: “None of the obligations set forth in the resolution shall be interpreted so as to conflict with or alter the rights and obligations of State Parties to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, the Chemical Weapons Convention and the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention or alter the responsibilities of the International Atomic Energy Agency or the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons”

Participants in International Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Law

This video lecture covers the following topic:

- the participants in international non-proliferation and disarmament law: states, international organizations, and individuals

Participants: Focus on the IAEA

1956 IAEA Statute

The IAEA Statute is the treaty establishing the IAEA. It provides for its objectives, functions, membership, structure and organs, activities, finance, privileges and immunities, and relationship with other organisations.

It was approved on 23 October 1956 by the Conference on the Statute of the International Atomic Energy Agency, held at the Headquarters of the United Nations.

It came into force on 29 July 1957.

As of April 2021, there were 173 States Parties to the IAEA Statute, or in other terms 171 IAEA Member States. For more information see also LU 05: Nuclear Weapons II .

IAEA functions

According to Article II of its Statute, the IAEA shall promote the peaceful uses of atomic energy while making sure it is not used to further any military purposes.

Non-nuclear-weapon States Parties to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (those that have not manufactured and exploded a nuclear weapon or other nuclear explosive device prior to 1 January 1967) have undertaken to conclude so-called “safeguards agreements” with the IAEA, for the exclusive purpose of verification of the fulfilment of their non-proliferation obligations under the treaty with a view to preventing diversion of nuclear energy from peaceful uses to nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices.

NPT safeguards agreements are separate bilateral treaties concluded between NPT States Parties and the IAEA. They provide for the application of measures such as inspections.

IAEA as a legal person under international law

The IAEA possesses legal personality. It has the capacity (a) to contract, (b) to acquire and dispose of immovable and movable property and (c) to institute legal proceedings.

It enjoys privileges and immunities necessary for the exercise of its functions. This means, for example, that the property and assets of the IAEA cannot be the object of search, requisition, confiscation, expropriation and any other form of interference, whether by executive, administrative, judicial or legislative action. This also means that IAEA staff such as inspectors cannot be arrested or detained while exercising their functions.

Non-Compliance and Disputes in Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Law

This video lecture covers the following topics:

- reminder of LU 13: Compliance and Enforcement

- definition of legal dispute

- means to settle legal disputes

- the role of the International Court of Justice

The UN General Assembly resolution dates to 15 December 1994. It was received in the Registry by facsimile on 20 December 1994 and filed in the original on 6 January 1995.

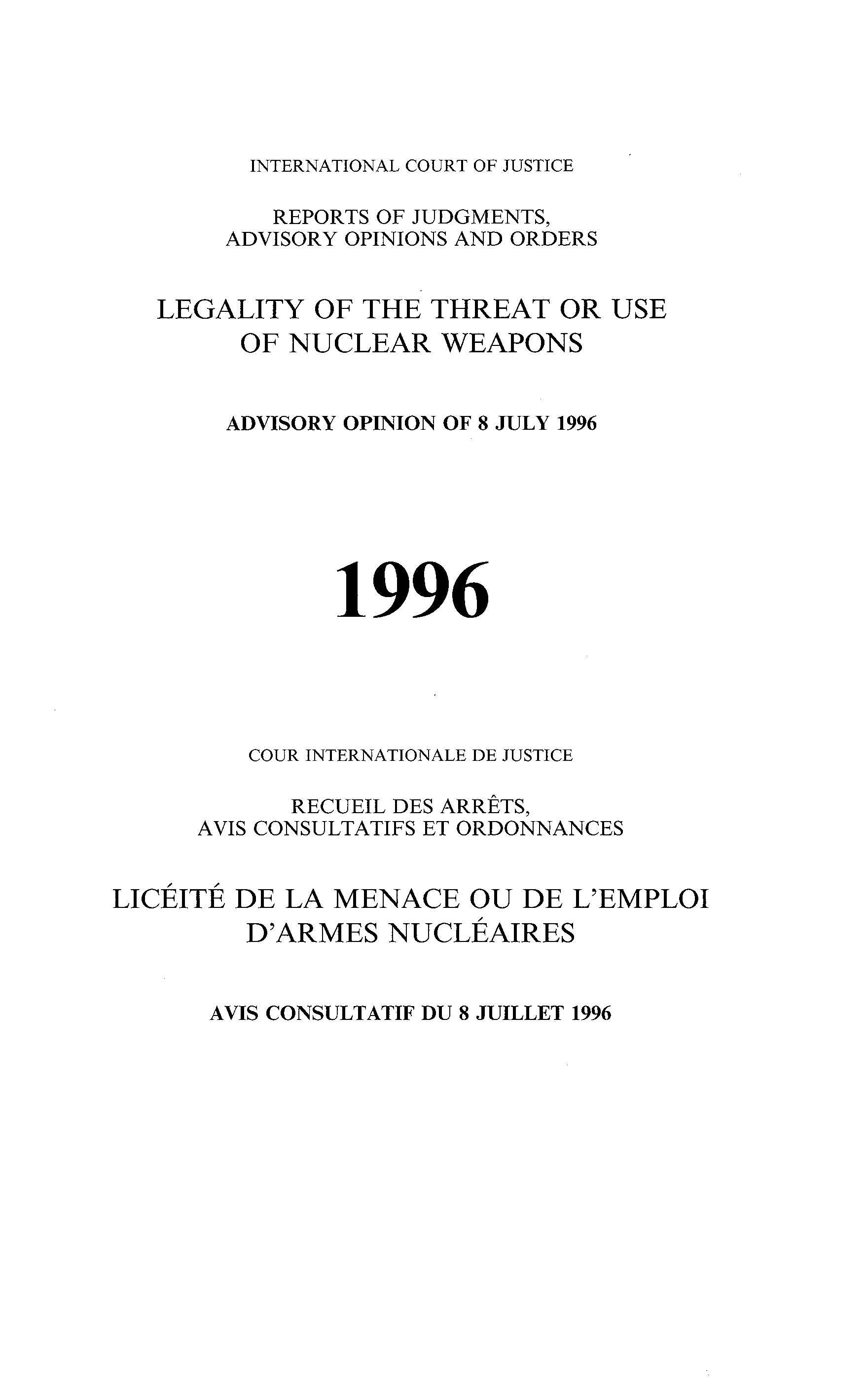

The International Court of Justice’s Advisory Opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons, 8 July 1996 (I)

A divisive advisory opinion

The ICJ’s Advisory Opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons has received much attention in the international legal, as well as non-proliferation and disarmament communities. The Court’s function was not to settle – at least directly – a specific dispute between states, but to offer legal advice on a specific question. Its divisive response was commented on by judges and scholars, but also governments of nuclear and non-nuclear-weapons states. As with other advisory opinions, many of the opinion’s passages are given weight as a source of international law.

The ICJ’s Advisory Opinion of 8 July 1996. [insert link](See the full document here).

The institution and question before the Court

In its resolution 49/75K adopted on 15 December 1994, the UN General Assembly requested the ICJ urgently to render its advisory opinion on the question: “Is the threat or use of nuclear weapons in any circumstance permitted under international law?”

Resolution 49/75K mentions the UNGA’s conviction that the complete elimination of nuclear weapons is the only guarantee against the threat of nuclear war; it also recalls the need to strengthen the rule of law in international relations as well as the recommendation of the UN Secretary General to take advantage of the advisory competence of the ICJ.

The Court noted that the question had relevance to many aspects of the activities and concerns of the General Assembly; including those relating to the threat or use of force in international relations, the disarmament process, and the progressive development of international law.

The International Court of Justice’s Advisory Opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons, 8 July 1996 (II)

The applicable law

According to the Court, the following is the most directly relevant applicable law governing the question of the legality of the threat or use of nuclear weapons:

- law on the use of force, which includes the use of force by states in self-defence (see Chapter 2 for more information)

- law of armed conflict, also known as international humanitarian law (see Chapter 2 for more information)

- treaties on nuclear weapons, including the NPT and regional nuclear weapon free zones treaties (see Chapter 2 for more information on treaty law)

The Court noted the “eminently difficult issues” arising in applying the law to nuclear weapons.

The ICJ, The Hague. Church-alike building with belltower and arch at the entrance.

The Court’s response

The Court addressed separate aspects of the question leading to its final following response which was adopted by seven votes to seven with the ICJ President’s casting vote in favour:

the threat or use of nuclear weapons would generally be contrary to the rules of international law applicable in armed conflict, and in particular the principles and rules of humanitarian law; However, in view of the current state of international law, and of the elements of fact at its disposal, the Court cannot conclude definitively whether the threat or use of nuclear weapons would be lawful or unlawful in an extreme circumstance of self-defence, in which the very survival of a State would be at stake.

?.

The judges were unanimous in their response that their exists an obligation to pursue in good faith and bring to a conclusion negotiations leading to nuclear disarmament in all its aspects under strict and effective international control.

Further reading: J. Burroughs, ‘Looking Back: The 1996 Advisory Opinion of the International Court of Justice’, Arms Control Today, July/August 2016.

Specificities of International Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Law

This video lecture covers the following topics:

- technical nature of international non-proliferation and disarmament law

- the importance of verification

- the number of sub-areas of international non-proliferation and disarmament law

- the number of relevant international instruments and institutions