The Genesis

From Early Initiatives to the Maastricht Treaty

EU countries have been cooperating in the foreign and security area since the early 1970s within the framework of the European Political Cooperation Process (EPC). In addition, some elements of common external engagement in economic terms, in particular trade and aid but also political-diplomatic engagement, date back to the 1960s.

With the entry into force of the Maastricht Treaty in 1993, the EU adopted and implemented a Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) under which member states sought to agree on foreign and security policies. Since the 1990s, the EU has sought to promote certain standards such as multilateralism, a rules-based international system and respect for human rights. As such, the idea of Europe as a standard-setting power has generated a great deal of work on the type of power the EU holds.

Superpower or “Civil Power”?

The launch of the CFSP and then the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP, formerly the European Security and Defence Policy, ESDP) in 1999–2000 sparked a debate on whether the EU could become a full-fledged power in the strategic sense of that term. The 2000s made it clear that the EU was not becoming a new superpower. With almost 30 CSDP missions in the early 2010s, the EU has not become a major global power.

In contrast, the EU could be characterised as a “civil power,” a “normative power,” or an illustration of the exercise of “soft power.” These three concepts help to capture significant elements of the character and behaviour of the EU as an international actor. The exercise of diplomatic pressure and the intensive use of the imposition of economic sanctions to persuade a third party to change its behaviour are also now historical features of the EU’s external action.

A Focused Approach

The EU’s contributions to the various non-proliferation and global security agendas at regional and global level were not absent from European action before 2003 but remained fairly concentrated. They concerned in particular the strengthening of the nuclear safeguards system under Euratom, the research initiatives taken by the Joint Research Centre (JRC), and the Commission’s actions to support former military scientists in the USSR in their civilian conversion.

The Security Architecture in Europe: CFE, VD and OST

The development of a strictly European strategy took place in parallel with the adoption, in a bilateral and in a European framework outside that of the EU, of a number of instruments designed on the one hand to ensure strategic stability on the continent and on the other hand to provide a framework for conventional armaments in Europe in the last years of the 20th century and the first years of the present century.

In the first case, the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, which in 1988 put an end to the so-called Euromissile crisis, was the first bilateral US–USSR and then Russian strategic disarmament treaty. This Treaty became one of the main symbols of the post-Cold War era and what has been called for more than twenty years “the peace dividend.”

In the second case, along with the Conventional Forces Europe Treaty (CFE; 1990) and the Vienna Document (VD; 1990, updated in 2011), the Open Skies Treaty (OST, 1992) constituted a mutual reinforcing framework of arms control and confidence and security building measures (CSBMs) in Europe.

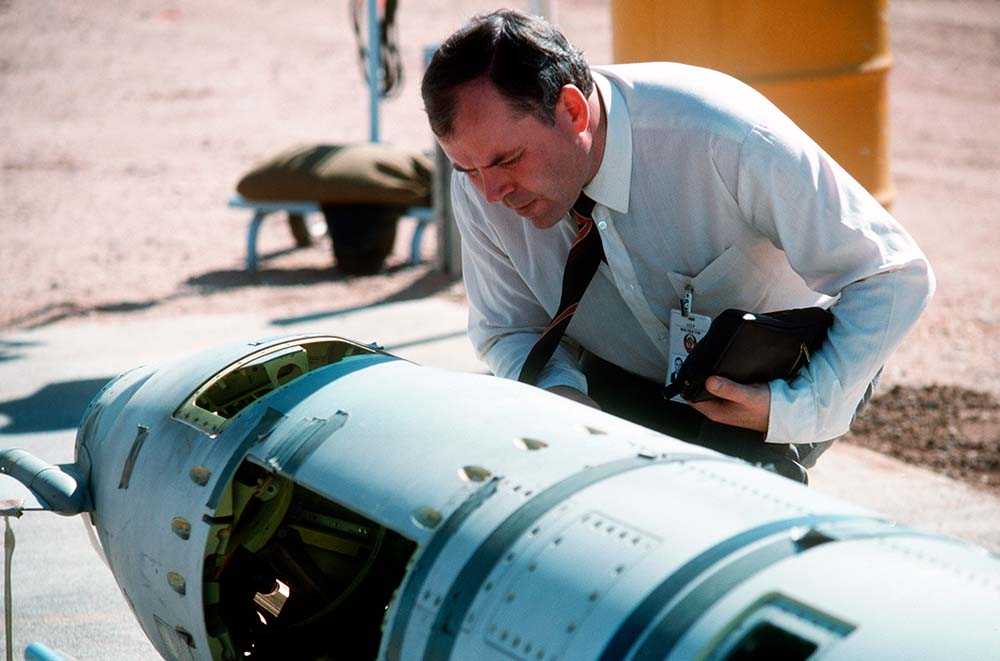

A Soviet inspector examines a BGM-109G Tomahawk ground launched cruise missile (GLCM) prior to its destruction.

For almost two decades, these three instruments have underpinned the security and stability of Europe as far as conventional weapons are concerned, having both symbolic importance and significant effects on the ground. For example, the CFE Treaty has resulted in the destruction of more than seventy thousand weapons systems; more than five thousand on-site inspections have been carried out and tens of thousands of notifications concerning exercises and military movements were exchanged between parties.

Enlarging the Union: Harmonising Export Controls

The main change with regard to the EU at the beginning of the century was the enlargement of the Union from 15 Member States in 2003 to 25 Member States in 2004 and then 27 in 2007. This changed not only the internal balances and processes of the Union, but also and primarily the strategic environment of the EU as an area of free movement of goods and people.

Thus, the priority was first of all to harmonise the export control policies of the new entrants so that all were aligned with the guidelines of the multilateral control regimes: Wassenaar Arrangement (conventional weapons and dual-use goods and technologies), Australia Group (biological and chemical goods and technologies), Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG, nuclear goods and technologies), Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR).

The European WMD-Strategy (2003), the ESS and the Action Plan

The adoption of the 2003 WMD Strategy marked the institutionalisation of the non-proliferation objective in the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). It was accompanied by the adoption of two other important doctrine documents: the European Security Strategy (ESS) and the Action Plan for the implementation of the basic principles of a European strategy against the proliferation of WMD.

At the Thessaloniki Summit, the European Council adopted a declaration on the non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. Building on the basic principles already established, Member States committed themselves to further develop, before the end of 2003, a coherent EU strategy to address the threat posed by proliferation and to continue, as a matter of priority, to develop and implement the relevant Action Plan adopted by the Council in June.

Council of the European Union

Latest Developments and Questions

The implementation of effective multilateralism by the European Union since 2004 has come up against several obstacles:

- proliferation crises in Iran and North Korea, which have highlighted the privileged place of the United States in major international disputes

- a reduced appetite of major states for multilateral solutions to international security problems

- the disintegration of strategic bilateral arms control between the United States and Russia in the course of the decade 2010

In addition, several prohibition norms were undermined in the second part of the decade 2010, particularly the norm of prohibition of chemical weapons in the context of the conflict in Syria.

Outside its borders, the EU still knows how to promote international instruments, whether legally binding or not, such as the NPT, the ATT, or the Code of Conduct against Ballistic Missile Proliferation, but its know-how is never as good as when cooperation and assistance can flourish on favourable ground. In critical situations, EU states always find it hardest to act together and/or effectively (North Korean crisis, Iranian crisis, Ukrainian crisis, European security crisis).

From this point of view, the EU is not yet a global strategic actor in the sense that a state defends national strategic ambitions with the support of proportionate military means on various regional scenes where it identifies interests. It must be noted that European “soft power” has not produced any gain in power. This raises the question of the meaning of European action in the field of non-proliferation and disarmament today and in the 2020 decade. Is the EU merely a bridge-builder between states with opposing positions? Or on the contrary, does the EU now have to defend specific and clearly identified European interests? This question drives the most recent arguments on arms control in Europe, against the backdrop of the debate on European strategic autonomy.